George Willard Bradley

George Willard Bradley and Ella Canote Miller

The following information was paraphrased from the book, Bannock Valley, by Laurie Jean Ward (pp. 178-180); the information was provided by Rene Bradley.

George Willard Bradley was born September 13, 1872 in Charleston, Kalamazoo, Michigan. George left school at age seventeen and headed West. He supported himself by breaking horses, shearing sheep, and being a cowhand. He rode some of the worst horses ever born, and prided himself that he had never been thrown off.

In August 1897 he wrote a letter to his mother, Julia, back in the Midwest. He said he was in Big Elk, Montana, making a living by breaking horses and shearing sheep. He had a lust for adventure, and told others that in the winter of 1899 he explored Yellowstone Park on snowshoes.

Like the iconic Hollywood western cowboy, George was known for always wearing two six-guns on his belt. An Arbon neighbor, Hanna Brower, said she never once remembered George sitting with his back to a door, but always faced it. No one in the family has been able to ferret out the reason for this, but it is interesting because it reminds one of the western movie, Shane, with its gun-fighter protagonist.

By 1900, George was in southeast Idaho. He must have liked what he saw, so in the winter of 1901-1902 he applied for a homestead in the Rattlesnake Creek drainage area of Bannock Valley (later called Arbon Valley). The Rattlesnake area was officially part of the Crystal part of the valley. He was able to get 160 acres under the Homestead Act. He had to live on the claim for the next five years. In the west, this meant for at least four months each year, as the government acknowledged the brutal winters and lack of educational facilities for families.

Pursuant to his other requirements, he built a homestead cabin and made improvements on his claim, clearing land and building fences. This cabin he built between 1899 and 1900 is still on the original homestead, and in pretty good shape for its age. The Rattlesnake area was opened for actual homesteading later than down in the valley, so for a period of time he was still “squatting†and did not get a free and clear title to his land until 1911, five years after the Rattlesnake area was officially opened for actual homesteading. His granddaughter-in-law, Rene Bradley, stated that for many years he was very reluctant to leave his land for any length of time, afraid that someone would come in while he was gone and move the land stakes that defined his claim.

In 1905, George registered his livestock brand with the state of Idaho. His was the Lazy Four brand. He paid a fee of $1.00. (The cost of registering a brand in Idaho nowadays is seventy times more!)

At some point, George’s mother Julia moved to Idaho to keep house for him. Her husband John, George’s father, had died in 1908. Julia also took up homestead land in the same area. Some time after George’s marriage to the local schoolteacher, Ella Canote Miller, in 1918, Julia sold her land holdings to her son and went back east to Indiana where she still had family.

Ella was born 27 April 1889 in Ottawa, Kansas, to parents George William Miller and Laura Bell Shreves Miller. She graduated from the Ottawa School of Business in 1915. Her brother had come to Idaho the year before and had written that school teachers were needed there. So she headed to Idaho.

Letters Ella sent back to her family in Kansas tell much of her experiences in the wilds of Idaho. School teachers back then sometimes boarded with different families in their district, sometimes moving from family to family either week-to-week or month-to-month in order not to be a burden on any one family. In Ella’s case, she appeared to stay with one family, and paid for her room-and-board. She was very pleased to have her own room complete with its own wood stove. She wrote home, “Board $18 per month, more than I ever had to pay before. But everything is higher here. People do not sell eggs, at least in winter time, for they have none to sell. They do not have chickens on account of coyotes. They do not sell cream and I never see any butter except when I go to Mrs. Bradley’s. People raise wheat mostly. Some cattle and hogs are raised. Mr. Bradley has more stock than anyone I know, he has 53 head of horses and cattle and 60 or 75 hogs.†Mention of Mr. Bradley attests that she had already noticed the handsome bachelor George Bradley. She also recorded her feelings for Mrs. Julia Bradley, writing home about Mrs. Bradley making eleven loaves of bread to take to a neighbor who had had to have a toe amputated.

The next year, Ella taught in the same school. The school was one room, with eight grades, with Ella the only teacher, and included grades one through eight. (This school still exists, but is now a private home on Mercer Creek, going north from Rattlesnake Road.) By now she had moved her residence to George Bradley’s cabin, which included his mother. With such close proximity, either love or hate was sure to follow. In this case it was love. George and Ella were married 1 March 1918 in Blackfoot, Idaho.

When he was planning on marriage, George started to build a new house in 1915. This “lumber†house was a few feet from the homesteading cabin, and had many modern innovations. (This is also still standing, on the Bradley Ranch headquarters, next to the homestead cabin).

This three-room house had two bedrooms and a combination kitchen-sitting room, built over a cement-walled storage cellar. To get to the cellar, there was a door on the side of the house instead of having the cellar door flush with the outside ground, which would have made the cellar inaccessible during the winter months when there could be five feet of snow on the ground. “In the cellar, left-over food was places in a screened in cupboard instead of our present-day refrigerator. The cellar also had shelves holding jars of canned fruits and vegetables, crocks filled with pickles and sauerkraut sat on the floor. Potatoes and onions were also stored there†(p. 179). The wonderful food storage attests to the talents and skills of George’s mother.

George’s innovative mind applied to other parts of the house also. “There was a spring above the house from which George piped water into the cellar and up to the kitchen sink… To him it was the best drinking water in the world. This cellar [also] held the separator which separated the cream from the milk. The cream was stored in cans of several gallons, which were taken into Pocatello to be sold. Some of the cream was saved to be churned into butter†(p. 179).

Another innovation was electricity. George diverted “Rattlesnake Creek to run over the hill below the house and over a water wheel, then back into the main stream. In this way he was able to create electricity to light the house†(p. 179). This battery was also stored in the cellar.

Homesteading was usually a “young men’s sport†but that naturally means the women who accompanied them were young and of a child-bearing age also. However, George was no spring chicken when he married Ella in 1918 – he was forty-five while she was twenty-eight.

Ella was somewhat surprised when faced with her first pregnancy in 1924, after six years of marriage, as by then she was thirty-five years old. Having a baby on a remote Idaho ranch presented certain problems that she wasn’t sure she could overcome. She went a long time brooding over her pregnancy before a neighbor woman asked her if she “was in the family way.†She confessed that she didn’t even know how to make clothes for a baby – back then, an expectant mother had to make everything, even diapers. The good Crystal women organized a sewing bee at the Bradley Ranch. They brought their sewing machines and made baby clothes and diapers. One woman even embroidered the edges of some of the little gowns, and later on taught Ella how to embroider herself.

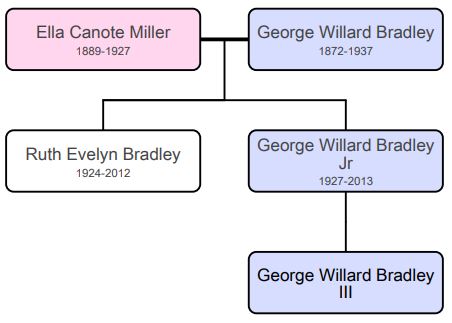

George and Ella’s first baby, Ruth Evelyn, was born 4 December 1924 in Pocatello, when George was fifty-two years old. Two and a half years later, the couple welcomed their second and final child, a son named George Willard Bradley, Jr. He was born on 27 June 1927, also in Pocatello, and was destined to eventually carry on the family ranch.

But the happy event of welcoming a new baby was soon overshadowed by a devastating event in the family. Ella died on 23 July 1927 when baby George was only a month old. The main cause was recorded on her death certificate as chronic nephritis, her condition exacerbated by her recent pregnancy. One source said she was so thrifty that money she was supposed to use to see a doctor instead she put in the bank. Perhaps this money she had saved later went to purchase her casket. Her body was returned to Ottawa, Kansas for burial.

George, at age fifty-four, was left with two young children, a toddler and a month-old baby. Neighbor women stepped in to help until Harold and Peggy Crump, with their three young children, soon moved in to help take care of the children for a while, and this was a very happy arrangement that lasted several years. Harold later purchased his own farm in Arbon Valley, and the two families stayed close.

Just over ten years later, tragedy again visited the Bradley family. The day before Christmas in 1937, George was killed in a car accident. His car slid off the American Falls overpass when he was returning home after shopping for Christmas gifts for his children. Ruth was twelve and George was ten. It was a very sad Christmas not only for the children but also for many neighbors in the valley. George’s body was returned to Augusta, Kalamazoo County, Michigan for burial.

George’s housekeeper at the time found some letters from members of George’s family with return addresses on the envelopes. She sent out telegrams to each of them. George’s sister Laura Bradley Haight came to get the children and took them back to Indiana where they lived until they were adults. The ranch was leased out to neighbors, Harold Crump and Herman Kruger.

When George Jr. graduated from high school, he joined the Marines. After his service, he returned to Idaho and decided to take up his father’s ranch again. He worked for Mr. Crump to learn how to ranch, and when the leases expired he took up ranching full time. Cattle smarts must have been in his DNA, as he was known as a very good rancher. He died in 2013 and was buried in the Arbon Cemetery. His son George Willard III now runs the ranch with his mother, Rene Bradley. They are known throughout Idaho for their registered Gelbvieh cattle.

Sources:

Ward, Laurie Jean, Bannock Valley (Providence, Utah: Keith Watkins and Sons, 1982).

https://www.familysearch.org/tree/person/details/KZMQ-RFR

https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/92306342

The links provided here will lead to information on other family members.