Jesse Nicholas Ward

Jesse Nicholas Ward and Julia Ann Moon

The Ward name has been in the Arbon Valley since 1893. In that year on May 15, Joseph W. Ward applied for both a possessory claim on Lake Canyon (directly west of the current Ward farmstead) and water rights in the same area, which at that time was called “Lake Creek†(Bannock Valley, p. 9). The subject of this history is Joseph’s younger brother Jesse. Jesse was only nineteen when he first came out to the valley in 1893, but he wasn’t old enough to claim ground until he was “of age†at age twenty-one. He completed one of the earliest homesteading claims in the valley in July 1906. Â

Jesse Nicholas Ward was born on 17 April 1874 in Snowville, Box Elder County, in Utah Territory. His parents were George Ward and Eunice Alice Nicholas. He was the fourth child, but one brother had died previously. Ten other children were born after him, five of which did not live to adulthood.

Jesse’s first cousin was Joseph Nicholas Arbon, after whose family the valley was named, as their mothers were sisters. These cousins were neighbors and friends in Arbon Valley all their long lives.

Jesse married Julia Ann Moon on 1 January 1896 in Henderson Creek, near Malad, Idaho. Julia was one of nine children born to Hugh Moon and Elizabeth Kemmish. Her parents were British converts to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints. They had married in 1854 in Utah in a polygamous arrangement.

Both Jesse and Julia came from good stock and were no strangers to hard work and trials. Julia’s father Hugh Moon was a respected frontiersman and horseman who had lived in Nauvoo, Illinois and had been a bodyguard for Joseph Smith. Hugh had traveled overland to Utah Territory in 1848. He was later one of the earliest settlers in the Malad Valley. An interesting note about Hugh Moon’s grave is that it was his dying wish that he be buried in Utah. The border between the two territories had not yet been surveyed, so those in charge of the burial picked a place they thought was on the Utah side. However when the border was later officially surveyed, Hugh Moon’s grave was found to be about six feet north of the border. (This grave can be seen on the Utah-Idaho border on Interstate 15, if you look east up the hill at just the right moment while you are flying by at 80 miles an hour. To see a picture of the headstone, see Hugh’s FindaGrave site on: https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/5044816/hugh-moon).

Julia’s mother Elizabeth had immigrated from England in 1853 with her family at the age of sixteen, coming the New Orleans route and up the Mississippi River to what is now the Omaha area before crossing the plains.

When Julia married Jesse, her father Hugh performed the ceremony which took place in her mother’s home. Their grandson Elmer Vance Ward wrote of his grandparents: “Jesse’s assets were mostly determination and courage, with the main asset of having a wife who was a…good homemaker; they both made the best with what they had†(Bannock Valley, p.93).

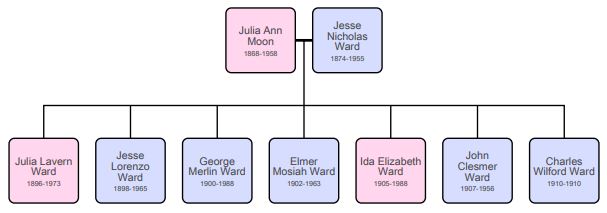

Jesse and Julie became the parents of seven children, six of whom lived to adulthood. These were Julia “Lavern,” 1896; Jesse Lorenzo, 1898; George “Merlin,” 1900; Elmer Mosiah, 1902; Ida Elizabeth, 1905; John Clesmer, 1907; and Charles Wilford, 1910-1910. Later in 1944 they adopted their grandson Eldon Thompson Ward.

In March of 1896, the same year of their marriage, Jesse and Julia moved out to Bannock Valley to reside on Jesse’s homestead, as per the homesteading requirements. Julia wrote her personal history when she was eighty-five years old. She remembered: “Jesse drove the cattle and four horses, Jesse’s brother little Tommie (who was nine years old) drove one wagon with the pigs, chickens, and some feed grain, and I drove the wagon with our household goods in [it]. On the way we stopped at the Benjamin Waldron store at Samaria, Idaho and purchased food supplies to last until fall. We camped at Ireland Springs, arriving at the homestead the next night†(Bannock Valley, p. 91).

Jesse, like all the early settlers, always called the valley “Bannock Valley,†named for the triangular peak that looms on the west side of the valley.

Julia wrote: “When we were married my brothers gave me a cow, a heifer and a yearling steer, and Jesse had three cows, so by 1905 we had a small herd of cattle†(Bannock Valley, p. 93).

“In the fall of 1896, and the summer of 1897, Jesse cut and hauled logs from Knox Canyon to build a large log room. The land wasn’t surveyed at that time and the house was build on the school section. [A neighbor] sawed out two doors and two windows. [Later,] after the land was surveyed the house was moved one mile west…More logs were added, making a two story house with a large bedroom upstairs…It has survived the hard winds and deep snow that fell in Arbon Valley and four generations [now six generations] of our family have lived in the house. We lived in the house until 1920. [Our son] Elmer Mosiah and [his wife] Susan lived in it until 1939, then when Elmer Vance and Edith were married they lived there†(p. 92). Vance and JoAnn, and their son Larin and both daughters-in-law also lived there. Not many people can say they have lived in a home that housed six generations (including Larin’s children) of their own family.

In the early days of the valley, many of the homesteaders kept the logs long on the corners of the cabins for a very practical reason – if someone got in trouble during a blizzard they could take refuge in the cabin (most families having moved to town for the winter months). That way the refugees would have easy access to firewood by cutting the log corners off the cabin. This unique but practical Arbon Valley habit was sometimes a shock to wives when they first saw their Arbon homes, as it made the cabins look very unfinished, even sloppy.Â

Julia wrote about their first home: “Our first home at the homestead was a small log room with a dirt floor. In a few days we had our straw tick [mattress] on a bed built to the wall, which was five feet high, [and] under the bed another bed could be made on the ground, [which was] also used to store supplies. Grandfather Ward [Jesse’s father, George Ward, 1844-1901] made our table and a wash stand, [and] a wooden box nailed to the wall with a calico curtain hung at the front was our cupboard. Grandfather Ward gave Jesse a stove they had bought in 1884. The summer and fall of 1893 they cut and hauled the logs from Lake Canyon and built the little log room, a barn for the horses, a cellar and a pole corral†(Bannock Valley, p. 91-92]. This first cabin is still on the Ward farm (moved to its present location in 1949), covered with white shingle siding, and five generations of Wards have started out married life in this home.

“In later years [Jesse and Julia] separated a small bedroom on the main floor and moved two rooms to the back for a bedroom and a front room†(as related by their granddaughter, Eileen Ward Estep, in Bannock Valley, p. 86).

Jesse’s grandson Elmer Vance tells of moving this cabin: “In 1949, Dad [Elmer Mosiah] and I put some logs under the homestead cabin we had been living in and pulled it with the crawler tractor a mile east. It was placed on a foundation with a small basement under it. Part of the Brahmstead house was added to it and a small back entrance hall was built.†At that time, it was covered in a brick siding (later changed to white shingle siding), and running water was installed, along with an indoor bathroom. It was heated with an oil stove (Bannock Valley, p. 89).

That first spring “There was snow on the ground every morning until the first of May. On the 29th of May, Jesse planted some corn, peas and potatoes. Jesse’s sister Eunice came out to the homestead the last of May and we milked fifteen cows twice a day.â€

About the hard work of homesteading, Julia wrote: “We were up in the mornings when the stars were still shining and worked late doing chores after dark. Jesse cleared the land of sagebrush and plowed most of the 320 acres with what [he] called a foot burner or an Oliver plow, drawn by two span of horses, guiding the plow with his hands. It was very slow [work], five acres of stubble land could be plowed in a day.”

Julia recorded: “When [the men] would take a load of wheat to Malad, they would get up at 2:00 or 3:00 in the morning. It would take four head of horses to pull the wagon. They would travel by way of the Turkey Trail, which they named well (it was very steep and winding). They would eat their lunch there, [and] they’d always take a salt shaker in the spring to have fresh watercress. They’d drive over into Malad, unload the wheat, and spend the night at Malad, then start back very early in the morning†(Bannock Valley, p. 86). These trips over the hills into Malad with a loaded wagon came to an end when the family purchased their first motorized vehicle, a Chevrolet truck, in 1926.

“Jesse freighted wheat from the homestead…to Collinston, Utah, receiving forty cents a bushel. The first wagon we had, we borrowed $100 in twenty-dollar gold pieces from my brothers Si [Mosiah Moon 1856-1948] and Joe Moon [Joseph Helaman Moon, 1861-1947]. It had a high spring seat, and when we went visiting neighbors, we traveled in this wagon for many years. Our nearest neighbors were the Andersen boys: John, Otto, and Maggs [Lars Magnus] who lived about one mile northeast…The Andersen boys used to come and watch me make cheese and churn the butter in an up and down churn. [My brothers] Joe and Si came a few times during the summer but I had very few women visitors during the summers I spent at the homestead†(Bannock Valley, p. 92).

Homesteaders in the early days often moved to town in the winters to avoid the harsh Arbon winters and provide school for their children. They sometimes got surprises when returning to their valley homes in the spring. New residents might be squirrels, pack rats, badgers, or skunks. One time Jesse and Julia got surprised with something somewhat larger than rodents. “In the spring of 1898 we arrived at the homestead late at night and found some sheep shearers were staying at the house. They had their beds made on the floor and they were shearing sheep in the barn and corral. The man that owned the sheep gave us seven little goats.†These goats were finally put in the Ward sheep herd – but only after they had [eaten] Julia’s best straw hat, played on the cellar until the roof fell in and knocked baby LaVerne to the ground every time she stepped out of the cabin.â€

On another spring-time return, “when they moved out to the homestead…a colony of rats were occupying the cabin. Every time Julie left the house she took LaVerne (who was a baby) with her because she was afraid the rats would eat her†(Bannock Valley, p. 93).

Homesteading in the remote valley of Arbon brought with it unique challenges. One of these was often the distance to medical doctors. Forty to sixty miles today takes less than an hour, but then could take two to three days, depending on the weather. “In February 1901, Jesse was operated on for a ruptured appendix. He spent six weeks in the hospital, a very sick man.â€

Another challenge was raising children. “When Merl [George Merlin] was two years old [about 1902] he went riding a stick horse while I was preparing breakfast. When I couldn’t find him my first thoughts were that he had fallen into the well. Jesse went down the well three times and couldn’t find him there. We then looked through the rye, which was about five feet high. We found him around noon almost to the top of the field. He was lost, tired, and crying.”

Life in Arbon at times could be like the Old West of the Hollywood movies. “One spring after we moved out to the homestead, a stranger called at breakfast time and asked if I would prepare him breakfast and a lunch of boiled eggs. He said he would pay me whatever I asked but he didn’t want any food that had salt on it. He asked if he could sleep in the chair while I prepared it. He would sleep a few minutes then go to the door and look around. He seemed nervous. When Jesse got ready to go to work the stranger asked the way to Malad, and started in that direction. Then the next morning before daylight I was awakened by the noise of someone drawing water from the well. Jesse went out and there was this same stranger. He said that the thunder and lightning was terrible in the hills and he decided to go to Rockland. I prepared him more eggs and he went north from our place. Jesse didn’t go to work; he decided the stranger was trying to locate a horse to ride so he brought the saddle and bridle into the house and turned the two horses into the field. We heard later [when Jesse] called at the store, they told him officers were looking for a man who had robbed the passengers and killed a man on a train. We never saw or heard of the stranger again.”

Another “old West†event that involved Jesse Ward happened in January, 1915. A homesteader named Julian Maes was well liked and had many friends in the valley. Unfortunately, he had fallen in love with a married female homesteader, Esther Westcott, who had recently become antagonistic towards him. He had visited with several neighbors that very day and had seemed perfectly normal. later in the day, he was able to sneak up on her cabin without being seen, as she had no windows on one side of her cabin so she couldn’t see his approach. She started running for her life, while her children, a son and a daughter, ages five and seven, ran the other direction to the closest neighbors for help. According to the newspaper version, “the couple ran for some distance, then Maes dropped to one knee, took careful aim and fired, with fatal accuracy, then running to where she lay, he placed the gun to his own chest and fired,†falling across her body. Neither one was killed instantly but they both lived only a little while. When neighbors later entered Maes’ cabin, they discovered a note addressed as “My Friends,†which explained his reasoning for doing what he did. He specifically named Jesse Ward as his friend and a man he trusted to administer his estate. Poignantly, he asked that his land be sold and the proceeds be giving to the victim’s orphaned children.

Another challenge to living in Arbon many might find surprising. According to Nelda Williams, her grandfather Jesse was once digging a well when it the sides of it caved in on him. “Granddad had the walls of a well he was digging cave in on him, pinning him to his hips. Though he was a large, strong man he was unable to move. His sons rushed in to aid him but Granddad, fearing more caving, demanded they stay out of the well. Fearing that he would be buried alive, however, they paid no heed to his warning and were eventually able to dig him free†(Bannock Valley, p. 97).

Jesse died on 25 April 1955 at the family home in Malad, Idaho at age eighty-one. He was buried in Malad. Julia died 27 January 1958 at age eighty-nine, also in the family home in Malad, and was also buried there. Julia was the very last survivor of all of her father’s family, which included three wives and twenty-seven children.

Elmer Mosiah Ward (1902-1963) took over the family ranch around 1920, consisting of 360 acres of the original homestead; he continued to build up the farm and buy more ground. His son Elmer Vance (1920-2010) took over the farm/ranch operation that included the original homestead. Elmer’s sons Vance and Darrel now farm the land with several of their children and grandchildren. Other connections were made in the valley, as Elmer Mosiah’s daughter Eileen married Louie Estep, an Arbon farmer, and his daughter Nelda married Sod Williams, who would become an Arbon rancher. Today the fifth generation of Wards and Williams continue farming and ranching in Arbon Valley.

Sources:

Ward, Laurie Jean, Bannock Valley (Providence, Utah: Keith Watkins and Sons, 1982).

https://www.familysearch.org/tree/person/details/KWC1-YDR

https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/97352975

The links provided here will lead to information on other family members.